One of the first Persephone books I ever bought was in the last century. Well, 1999, actually. It was about then they began to re-publish excellent books that had been allowed to go out of print. And what discoveries I have made between there and now; not only fiction, but glimpses into a different world, ranging from novels, both light and dark, cookery books, social history, social comedy, biography - you name it, they publish them. And not only from this side of the pond...

...which brings me to The Home-Maker by Dorothy Canfield Fisher. It is now being re-printed as the eleventh Persephone Classic. Looking back, I have a horrible feeling I didn't read it at the time, always intending to do so at a later date. Many I did indeed but somehow missed this one. No longer. And I love it.

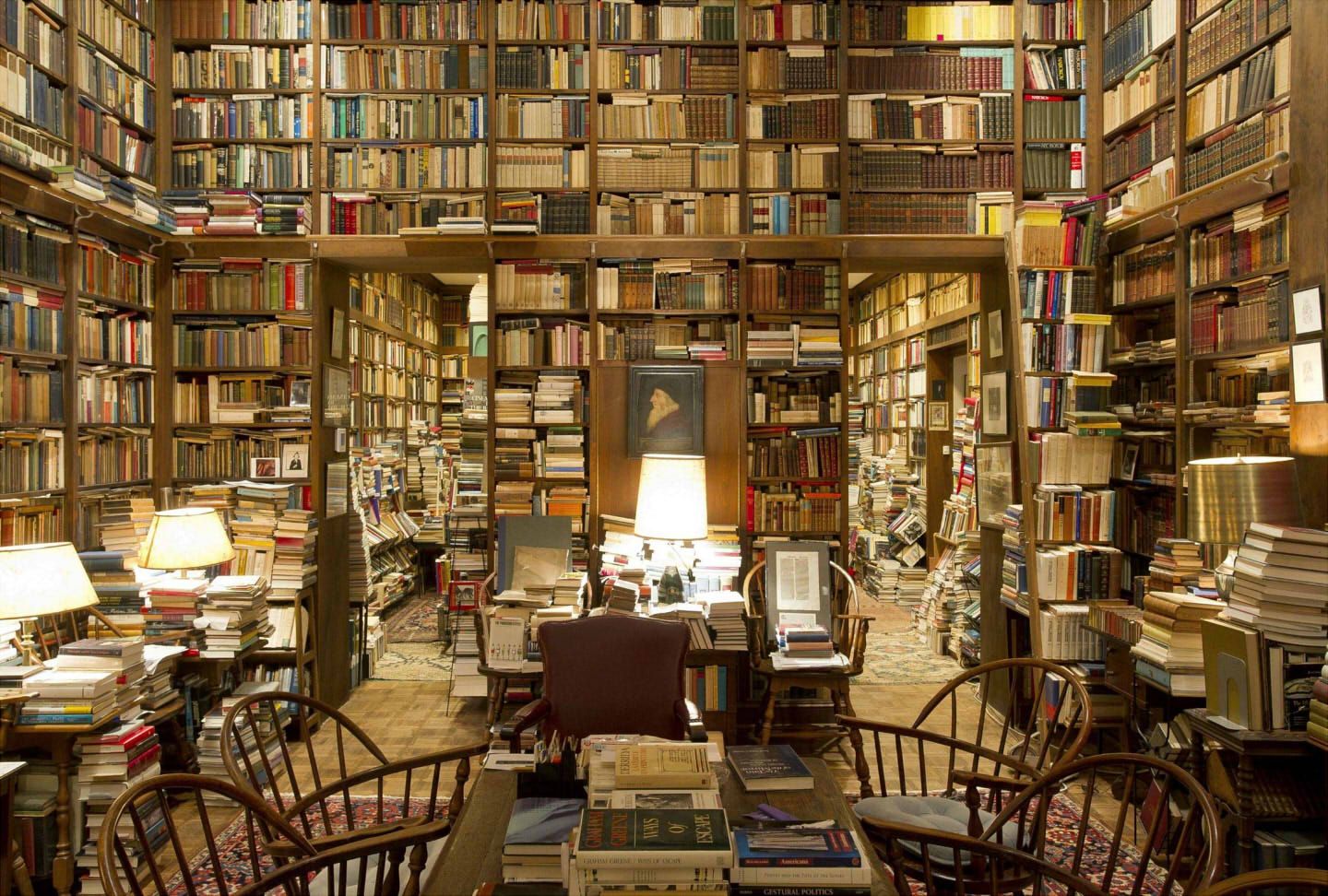

So, before I discuss The Home-Maker as a novel with characters, a plot and much to say, please pop over to Persephone Books and take pleasure in everything there is to know about these wonderful books.

Dorothy Canfield Fisher (1879-1958) was born in Kansas was a home-maker (in the UK we use the term, 'housewife') who also added significantly to the household budget by her writing. She was also an advocate of Montessori children's education system. Today, much of what it encouraged is seen as vital and, yes, normal. At the time when this book was written it must have sounded very odd. Not only were children not heard, they certainly weren't seen and more importantly, weren't actually listened to. Even today, it is still rare in many societies.

The society in which The Home-Maker is set is dominated, as one might expect, by church and chapel and the Ladies Guild. Everyone knows one another and all shop at the department store, Willing's Emporium, which sells everything. Events takes place not long after the end of the Great War. The novel concentrates on one family: Lester and Evangeline Knapp and their three children, in descending order of age: Helen, Henry and Stephen.

They are a loving couple we are told. As is de rigeur, Lester has a clerical job in the accounts department of Willings. Evangeline cooks and cleans and cares for the children. Helen and Henry attend school. Stephen is not old enough. Although they have enough to eat, they are well-clothed, thanks to Evangeline's talent with a needle and cooker. Only, all are miserable and some have medical problems. Lester loathed his job and is not very good. Both he and Henry have problems with their digestion and must eat bland food. The youngest, Stephen, is even though to be an impossible child, naughty, even wicked. He is prone to outbursts of hysterical crying and fits of wild anger. Even the perfect, clever, efficient Evangeline is always on the go and suffers from eczema.

Of course, there is a major crisis. (no plot spoilers here.) The result is that Evangeline becomes the wage-earner and Lester, the home-maker. And, with a twist at the end, their health and happiness, both mental and physical improve beyond measure. What begins as an emergency measure becomes essential. Many people have seen this as a novel that advocates women's rights, but this novel is as much about men's rights as well. What's more important the main thrust is children's rights.

As Lester thinks it through: "How about the children? Did anybody suggest to women that they give to understanding their children a tenth part of their time and real intelligence and real purposefulness they put into getting the right clothes for them? A tenth? A hundredth!" The living, miraculous, infinitely fragile fabric of the little human souls they live with - did they treat that with the care and deft-handed patience they gave to their filet-ornamented table-linen. No, they wring it out and hang it up to dry as they did their dish-cloths."

I actually find that Evangeline is the least sympathetic character in the novel. Even though she becomes a happy and fulfilled woman, who is also able eventually to love and enjoy her children, everything she stands for is far less interesting and impressive to me than what Lester learns about his children. I also fail to see that the marriage is a truly loving relationship because they never understand the truth of the situation at the novel's conclusion. They both realise the truth of the situation but they do not talk about it together. Perhaps the point is not so much them, but human society in general.

PS. I cared about Stephen the most. To me he is the most interesting, engaging and sympathetic character in the whole novel. Lester notices that, despite his early struggles handling his intelligence, he is the outstanding member of the Knapp family. Many other readers have remarked on the scene where Lester watches him learning to handle the mechanics of an egg-whisk (without any egg). You must read this short section, if nothing else, if you want to understand the beast way to understand children learn without adult intervention (or rather) interference.

No comments:

Post a Comment

I welcome all comments even if they disagree with my opinions - but only if they are friendly and add to the discussion. I will delete pdq any spam, insults or total irrelevancies.